We’ve all experienced inflammation in our bodies. We get a paper cut and a finger becomes inflamed at that spot—it seems for days on end—before healing. We twist an ankle and the area becomes red and swollen (inflamed); but a little ice, rest, elevation and over time the area is as good as new.

becomes inflamed at that spot—it seems for days on end—before healing. We twist an ankle and the area becomes red and swollen (inflamed); but a little ice, rest, elevation and over time the area is as good as new.

In this sense, inflammation is a good thing. It’s the body’s natural defense and indicates a healthy immune system response when injuries or infections occur.

But what happens when our WHOLE BODY becomes inflamed? I’m not talking  about an autoimmune disease that exhibits itself in specific areas of the body—such as psoriasis, celiac disease, or rheumatoid arthritis—and makes itself known for all to see, a sort of medical shout out that says, “Look here! This is runaway inflammation.”

about an autoimmune disease that exhibits itself in specific areas of the body—such as psoriasis, celiac disease, or rheumatoid arthritis—and makes itself known for all to see, a sort of medical shout out that says, “Look here! This is runaway inflammation.”

I’m talking about a silent killer—chronic inflammation. Recently, I had a routine medical check-up with my primary care physician and, as part of the process, blood was drawn and specific lab results were reported. One of the things my doctor looked at was my C-reactive protein lab result. He was happy to see it within normal limits and made sure to comment on that since that’s an indicator of chronic infection and one of the indicators for heart disease.

For many years, cardiologists have focused on heart disease as a plumbing repair issue—clogged arteries due to cholesterol build-up that narrows and then blocks those arteries near the heart must be cleared. In the early years of modern cardiac disease management, it was believed that the cholesterol we eat caused the build-up in our arteries.

In later years, it was discovered that certain fats we eat (saturated fats and trans fats, specifically) caused the body to make much more cholesterol than necessary. Hence, the popularity of cholesterol-lowering drugs such as Lipitor and the advancement of procedures to unblock clogged arteries. In this sense, cardiologists became sophisticated “Roto-Rooter” plumbers.

Recently, a series of interesting articles reported an evolving science that indicates there is much more involved regarding cardiac disease than the idea of clogged pipes (arteries).

The studies that shed light on this evolving science indicate that a possible primary cause of coronary artery disease is chronic inflammation—a so-called systemic inflammation that causes scar tissue in our arteries that begin to trap fatty particles (cholesterol) from our blood. That’s why my physician was happy to see my C-reactive protein lab result within normal limits.

primary cause of coronary artery disease is chronic inflammation—a so-called systemic inflammation that causes scar tissue in our arteries that begin to trap fatty particles (cholesterol) from our blood. That’s why my physician was happy to see my C-reactive protein lab result within normal limits.

Presently, there is a clinical trial of a new drug called Canakinumab, a drug that reduces systemic—or low-grade, total body—inflammation. The clinical trial is called the Canakinumab Anti-Inflammatory Thrombosis Outcomes Study (CANTOS). The study results indicate that this drug lowers heart attack risks independent of cholesterol-lowering medications, like the statin drug Lipitor.

Patients on Canakinumab experienced an astounding 30% decrease in the need for invasive and expensive bypass surgeries and angioplasty procedures. This represents a whole new level of cardiac disease prevention and brings in a third tier of heart attack prevention (the first two measures being the importance of diet and exercise, and then the additional layer of protection with cholesterol-lowering statin drugs).

An interesting additional benefit of this drug was a documented decrease in cancer risk by 50%. Researchers now question if the idea of reducing systemic inflammation throughout the body may not only prevent the onset of cardiac disease but also become a cancer prevention measure. This has stimulated a whole new area of cancer research, but it’s too early to get excited about that possibility at this point.

It should be noted that since Canakinumab lowers the body’s immune system response,  this drug may have a detrimental effect by increasing the risk of common infections becoming more serious, and even fatal, events. So, the benefits of this new therapy will have to outweigh the possible disadvantages, and further research may discover ways to minimize the infection-related risks.

this drug may have a detrimental effect by increasing the risk of common infections becoming more serious, and even fatal, events. So, the benefits of this new therapy will have to outweigh the possible disadvantages, and further research may discover ways to minimize the infection-related risks.

Thoughts? Comments? I’d love to hear them!

Since I have a Master’s Degree in Nutrition, I was asked by my running club to give a talk this week to our training teams. The subject is proper nutrition for the long-distance runner. While researching information for that talk, I came across an interesting article in the New York Times.

Since I have a Master’s Degree in Nutrition, I was asked by my running club to give a talk this week to our training teams. The subject is proper nutrition for the long-distance runner. While researching information for that talk, I came across an interesting article in the New York Times. calories than you use, you gain weight. If you consume fewer calories than needed, you lose weight. The science is simple, but the execution of that is more difficult—for instance, I can never resist a piece of chocolate cake!

calories than you use, you gain weight. If you consume fewer calories than needed, you lose weight. The science is simple, but the execution of that is more difficult—for instance, I can never resist a piece of chocolate cake! These studies, although still difficult to extrapolate to humans at this point, suggest that one person might have bacteria in their intestinal tracts that consume more calories, leaving that person thinner. Whereas, another person might have a different bacterial mix and gain weight by consuming similar daily calories.

These studies, although still difficult to extrapolate to humans at this point, suggest that one person might have bacteria in their intestinal tracts that consume more calories, leaving that person thinner. Whereas, another person might have a different bacterial mix and gain weight by consuming similar daily calories. Many thrillers and murder mysteries rely on some aspect of DNA evidence to solve the crime. This is true in the make-believe world of written fiction as well as in movies and television. Certainly, it is true in the real world of forensics.

Many thrillers and murder mysteries rely on some aspect of DNA evidence to solve the crime. This is true in the make-believe world of written fiction as well as in movies and television. Certainly, it is true in the real world of forensics. medical examiner discontinued using two methods of “high-sensitivity testing” of trace amounts of DNA. These methods of analysis had been used for years and were considered cutting edge science by many. These methods were said to go beyond even the standards set by the FBI and other public labs for trace evidence.

medical examiner discontinued using two methods of “high-sensitivity testing” of trace amounts of DNA. These methods of analysis had been used for years and were considered cutting edge science by many. These methods were said to go beyond even the standards set by the FBI and other public labs for trace evidence. lawyers. The coalition recently requested the New York State inspector general’s office to launch an investigation to determine if the previous—and now discarded—DNA analysis techniques were flawed.

lawyers. The coalition recently requested the New York State inspector general’s office to launch an investigation to determine if the previous—and now discarded—DNA analysis techniques were flawed.

physical evidence linked the man to the attack on Mr. Patterson; but, the man was convicted for gang assault by the judge and sentenced to four years in prison. The man’s attorney is appealing the conviction and the potential for flawed DNA evidence will likely be used in this appeal.

physical evidence linked the man to the attack on Mr. Patterson; but, the man was convicted for gang assault by the judge and sentenced to four years in prison. The man’s attorney is appealing the conviction and the potential for flawed DNA evidence will likely be used in this appeal.

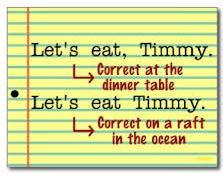

that anytime the writer intends the reader to break for a breath, that’s where a comma should be placed. But people breathe at different times when reading the same sentences, so that rule doesn’t hold up. For today’s discussion, a comma is used to separate phrases that intend to clarify previous words (such as, “He was a handsome fellow, with hair the color of gold.”).

that anytime the writer intends the reader to break for a breath, that’s where a comma should be placed. But people breathe at different times when reading the same sentences, so that rule doesn’t hold up. For today’s discussion, a comma is used to separate phrases that intend to clarify previous words (such as, “He was a handsome fellow, with hair the color of gold.”). interruption in dialogue or to emphasize a phrase in both dialogue and narration. It’s a much stronger punctuation mark than the comma but less formal than a colon, and it’s a more relaxed form of punctuation than the more technical use of a set of parentheses to explain or emphasize a specific point (such as, “He was a handsome fellow—with hair the color of gold that shimmered like the setting sun.”).

interruption in dialogue or to emphasize a phrase in both dialogue and narration. It’s a much stronger punctuation mark than the comma but less formal than a colon, and it’s a more relaxed form of punctuation than the more technical use of a set of parentheses to explain or emphasize a specific point (such as, “He was a handsome fellow—with hair the color of gold that shimmered like the setting sun.”). whether or not to use an ending period if the ellipsis comes at the end of a sentence. Most guidelines are satisfied with no final period.

whether or not to use an ending period if the ellipsis comes at the end of a sentence. Most guidelines are satisfied with no final period. Grammatical rules assure that uniform guidelines are followed so that the reader’s experience is all about focusing on the story rather than about negotiating unique writing styles. I should point out, however, that many writers have been successful with unique styles of writing.

Grammatical rules assure that uniform guidelines are followed so that the reader’s experience is all about focusing on the story rather than about negotiating unique writing styles. I should point out, however, that many writers have been successful with unique styles of writing. science thriller by an author friend of mine, Amy Rogers. The novel is called

science thriller by an author friend of mine, Amy Rogers. The novel is called

Hyphens and dashes are two distinctly different

Hyphens and dashes are two distinctly different

used in place of the word “to.” We can express an age range (from 40 – 60) or a distance (from New York – California) by using such a dash. It’s called the En dash because it takes the space of a lower case n in print. Usually, your computer will convert double dashes to an En Dash when adding a space between the previous word and the dashes and a space before the next word.

used in place of the word “to.” We can express an age range (from 40 – 60) or a distance (from New York – California) by using such a dash. It’s called the En dash because it takes the space of a lower case n in print. Usually, your computer will convert double dashes to an En Dash when adding a space between the previous word and the dashes and a space before the next word.

general anesthesia. It also decreases levels of consciousness along with a loss of memory for sedation during minor medical procedures. It is administered intravenously.

general anesthesia. It also decreases levels of consciousness along with a loss of memory for sedation during minor medical procedures. It is administered intravenously.

In animal studies, a 16-fold higher oral dose was needed to produce a similar sedative effect as compared to an intravenous dose. This is because of the drug’s limited water-soluble nature (oil soluble), and the fact that the stomach lining and liver filter out the potency of the drug before it can enter the blood stream.

In animal studies, a 16-fold higher oral dose was needed to produce a similar sedative effect as compared to an intravenous dose. This is because of the drug’s limited water-soluble nature (oil soluble), and the fact that the stomach lining and liver filter out the potency of the drug before it can enter the blood stream. In last week’s blog, I discussed how patients can take back control of their medication costs. I suggested

In last week’s blog, I discussed how patients can take back control of their medication costs. I suggested

The supply and costs of new medications are controlled entirely by the drug manufacturer that holds the patent rights. That’s a 20-year monopoly on a new drug before that medication could be offered as a less expensive generic version (competition). In that 20-year period, drug makers are free to increase prices as often and by as much as the market will bear.

The supply and costs of new medications are controlled entirely by the drug manufacturer that holds the patent rights. That’s a 20-year monopoly on a new drug before that medication could be offered as a less expensive generic version (competition). In that 20-year period, drug makers are free to increase prices as often and by as much as the market will bear. universal definition of a drug’s value, other than a drug that stands alone as the ONLY effective cure for a disease. Another possible added value for a new drug is disease control or a cure without drug interactions or side effects.

universal definition of a drug’s value, other than a drug that stands alone as the ONLY effective cure for a disease. Another possible added value for a new drug is disease control or a cure without drug interactions or side effects. An estimated 49% of Americans report using at least one prescription drug in the last 30 days, and a staggering 19% report that they have skipped taking a prescribed medication, or taken less drug than indicated, because of the drug’s high cost.

An estimated 49% of Americans report using at least one prescription drug in the last 30 days, and a staggering 19% report that they have skipped taking a prescribed medication, or taken less drug than indicated, because of the drug’s high cost. higher the copay. Ask your doctor if a drug that costs less would work as well. That less expensive drug usually means a drug in a lower tier that may work just as well. For me, I used to take a medication that was a combination of two drugs in one pill, and that combo was only available as the expensive branded drug. I found that by asking my doctor to order the two drugs separately instead of in the branded combo form, I could get the two drugs as generics and that saved me considerable money.

higher the copay. Ask your doctor if a drug that costs less would work as well. That less expensive drug usually means a drug in a lower tier that may work just as well. For me, I used to take a medication that was a combination of two drugs in one pill, and that combo was only available as the expensive branded drug. I found that by asking my doctor to order the two drugs separately instead of in the branded combo form, I could get the two drugs as generics and that saved me considerable money. plans these days have contracts with national pharmacy chains. The copay costs are often lower when you use these contracted (called “preferred”) pharmacies. Additionally, an estimated 36% of large employers have a preferred pharmacy that has agreed to provide extra discounts to their employees.

plans these days have contracts with national pharmacy chains. The copay costs are often lower when you use these contracted (called “preferred”) pharmacies. Additionally, an estimated 36% of large employers have a preferred pharmacy that has agreed to provide extra discounts to their employees. middle to allow an accurate split. There are also inexpensive devices available for purchase in most pharmacies that will split the pill for you. Please note that some medications are the time-release type, and these CANNOT be cut because it would allow the entire dose to be delivered at once rather than gradually. Always ask your doctor or pharmacist if a pill can be split safely before doing so on your own.

middle to allow an accurate split. There are also inexpensive devices available for purchase in most pharmacies that will split the pill for you. Please note that some medications are the time-release type, and these CANNOT be cut because it would allow the entire dose to be delivered at once rather than gradually. Always ask your doctor or pharmacist if a pill can be split safely before doing so on your own.